NOTE: This is a repost of an article I wrote for a newsletter column I am trying to get into the habit of writing.

Perhaps you’ve heard already: a startup has brought dire wolves back from extinction.

At least, that’s what Time (“The Return of The Dire Wolf”) and The New Yorker (“The Dire Wolf is Back’) reported with bold headlines. Both were given exclusive access to the story (we’ll set aside the semantic question of how can you be “exclusive” with two things at the same time). What they saw were genetically engineered white puppies, derived from gray wolves.

The catch? Dire wolves and gray wolves aren’t exactly cousins. They’re more like distant relatives who stopped talking millennia ago. So tweaking a few gray wolf genes probably doesn’t get you a dire wolf. But I try to be a practical person, which is why I find myself nodding to the company’s Chief Scientific Officer: “My colleagues in the field of taxonomy are going to be like, ‘It’s not a dire wolf,’” she says. “And that’s fine, but to me, if it looks like a dire wolf and it acts like a dire wolf, I’m gonna call it a dire wolf.”

The only problem with that logic is that no one has seen a dire wolf. No knows how they talked or acted. The newest fossils are over 13,000 years old. They vanished long before Egyptians were making blueprints for the pyramids. The only reason most people have even heard of dire wolves is because of a television show based on a book series written by a man who clearly hates writing.

So far, the two standout traits of these “resurrected” creatures are: 1. They are white. 2. They are sad. Here is the leading paragraph from the Time:

“Then there’s their behavior: the angelic exuberance puppies exhibit in the presence of humans—trotting up for hugs, belly rubs, kisses—is completely absent. They keep their distance, retreating if a person approaches. Even one of the handlers who raised them from birth can get only so close before Romulus and Remus flinch and retreat. This isn’t domestic canine behavior, this is wild lupine behavior: the pups are wolves. Not only that, they’re dire wolves—which means they have cause to be lonely.”

The criticism hasn’t stopped at behavioral melancholy. Many are asking: why do this at all? Why bring back animals that nature already voted off the island?

The counter-argument is rooted in “de-extinction”—the idea that Ice Age megafauna like woolly mammoths and dire wolves once anchored vast ecosystems, and that bringing them back might help restore ecological balance. Sure, the environment has changed, and these creatures likely wouldn’t survive in the wild today. But is that really a deal-breaker? Most people I know wouldn’t last a day without Wi-Fi, or more than a mile from a Trader Joe’s, yet here we are.

There are potential uses for these animals. Zoos. Circuses. Possibly even pets, once we’ve figured out how to make them less emotionally devastated. Personally, I’ve always wondered whether a dodo would taste like chicken—and whether reviving them might be a step toward lowering egg prices.

I would even be even more daring and suggest a personal wishlist for the animals I want:

- A pegasus (just a horse with a tiny bit of the flying gene) would solve many of my personal transportation problems

- A monkey that doesn’t fling feces is my idea of a perfect roommate.

- While we’re at it, bring back mermaids.

- And could we edit out the crying gene from babies? Or at least add an airplane mode?

For those shouting, “Why? Just… why? This is wrong. You’re playing God!”—well, the best response comes from Colossal’s Chief Animal Officer (man, I would love for a title like that).

“I think of that famous Teddy Roosevelt quote,” says James, paraphrasing the 26th President. “In the moment of any choice, the first thing to do is the right thing. The next thing to do is the wrong thing. The worst thing to do is nothing at all.”

Coincidentally, “doing the second-best wrong thing” is also the unofficial tagline of this blog.

Weight loss Miracles

Something special is happening in the world of weight-loss interventions. In a recent lecture, Dr. Louis Aronne, a leading authority on obesity at Weill Cornell Medical College, remarked that over the course of his career, he had conducted more than sixty clinical trials. Nearly all of them had failed—until the last few years.

I’ve always been wary of medications. I’m not fond of shortcuts. Let’s just say, I don’t trust miracles. I’ve believed, perhaps stubbornly, that the path to lasting happiness runs through suffering, or at least self-discipline and the gym. But hearing a medial authority talk on the subject has nudged in a different direction.

Weight loss, I am told, is not a matter of willpower—it’s a neurological problem. There’s a feedback system between the gut and the brain that’s supposed to tell us when to stop accumulating mass. In many people, that channel is broken. No amount of running or intermittent fasting can fix a communication failure in the brain. Asking someone with this kind of dysfunction to lose weight by diet or by exercise it like telling someone with acute hypertension to just relax and meditate instead of prescribing them with medication.

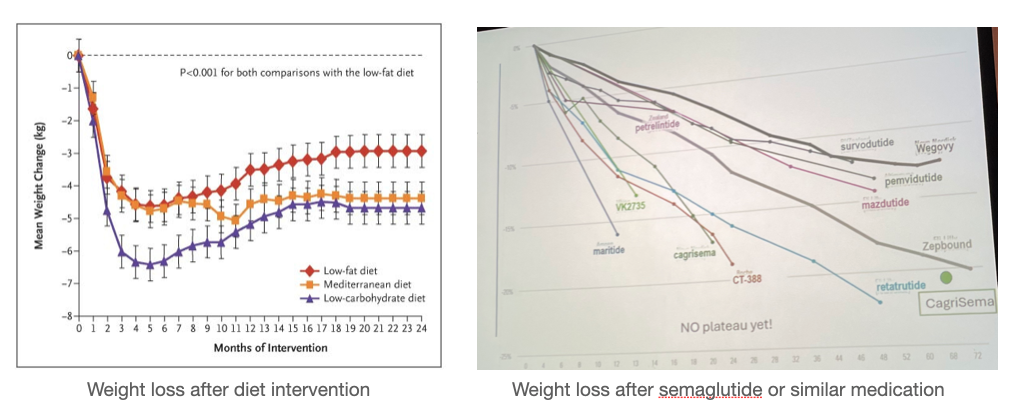

Just to show how bad diet interventions are how effective the modern treatments are, consider the following plot. On the left, we have the results from a study from 2008 which randomly assigns a low-carb diet to moderately-obese subjects and studies their weight-loss patterns. On the right, we have the result of modern medicine (similar to Ozempic). On both are plotted percentage weight-loss against the weeks after intervention.

As you can see, even with a very strict diet-intervention (adherence rates of 95% in first year, and 84% in second year), the weight loss is smal, only about five percent. You see a drop in weight and soon, the body readjusts to the new diet and you start gaining weight again. On the other hand, if you used one of these new drugs like Wegovy or Ozempic, the weight loss is significant (up to 35 percent weight loss) with no signs of it plateauing.

And its not just weight. These drugs seem to improve everything: cardiovascular health, diabetes risk, addiction behaviors. Almost any health marker you care to track shows a positive shift. At first, when people told me this, I assumed there had to be a catch. There’s always a catch. The researchers respond saying “Look, we have been looking. We have already spent a long time trying to find all the side-effects and catches. But, except for the basic palette of common side-effects, we haven’t found anything devastating.“

So, perhaps miracles are real. I will, for sure, open my mind up a little bit more.

There is a whole new field of research of people trying to cure disease X with medication Y meant for a wholly different disease. For example, a new paper in Nature shows that Herpes vaccine could reduce chances of dementia. Isn’t that just cool?