NOTE: This is a repost of an article I wrote for a newsletter column I am trying to get into the habit of writing.

After a month on the road, I am finally home again — haunting the banks of the Hudson. And, I am simply overwhelmed by your support of this project: the texts, the emails, the subscription pledges. Thank you from the bottom of my heart — you inspire me to write as often as I can.

I don’t do this to be read by hundreds, nor with the slightest intent of earning anything. I write this so, when our paths cross, we will have something to bicker about. I write this to not forget, in this age of ChatGPT, the joy of putting together sentences. If these words offer you a slightly more bearable experience than scrolling Twitter, I shall call it a job well done.

As you may have heard, the Conclave has elected a new pope. The first I heard of the Conclave was in high school, and even then I found the idea a little funny: a bunch of guys go in a room to elect their next leader — sometimes in two days, sometimes over three years. The pictures coming out of Vatican also brought back vague memories of college days. Sure, we too used to have a conclave of sort. A handful of friends (plus one or two outsiders) locked in a room with billowing smoke. We too were deciding on some question. I don’t recall what exactly but something stupid like whether to haul overflowing trash down the stairs or to flight it down the window right into the dumpster (the dumpster would eventually catch fire in a separate incident). In our conclave, we resolved these dilemmas with a coin flip, or the roll of a die. Which brings me to the question: why doesn’t the Catholic Church elect its leader randomly from a pool of eminently qualified cardinals, using say a lottery machine?

This is not a particularly strange proposition. In 2012, the Coptic Orthodox Church in Egypt picked its patriarch by having a blindfolded child draw a name from a jar. In 1793, when the Qing dynasty strengthened its hold of Tibet, it demanded that Tibetan religious leaders be chosen randomly from Golden Urns, as opposed to the tradition of reincarnation. Such random selections appear to be fairer, more transparent, less susceptible to corruption. Yet the Catholic church has vehemently resisted such measures. There is, of course, St Thomas Aquinas’s tirade in Summa Theologica against randomness, or augury, or any kind of divination in church affairs. Even decades before Aquinas’s writings, in the thirteenth century, Pope Honorious III would end up prohibiting random selections in all ecclesiastical offices. Their argument boils down to this: randomness is antithetical to God’s will, which, oddly enough, echoes Einstein’s quip in a completely different context: “God does not roll dice.” Sure! God much prefers making decisions through petty politics and an extremely corruptible process. (For those curious about the unsavory side of the papacy, I highly recommend Sarah Dunant’s In the Name of the Family or the TV series Borgia.)

The reason I am even thinking about this is that I have lately been interested in randomized processes for election, and I had a meeting with Ariel Procaccia who works towards engineering democracies to be more efficient — how to randomly select public officials, how to optimally resettle refugees, or how to mathematically fix gerrymandering. I am mainly interested in his work on organizing citizen assemblies, where, one challenge is this: even when we would like the public to directly participate in decision making, it is usually the overly educated and those with ample leisure time who turn up, introducing bias and undermining true representation. His lab at the Harvard engineering school develops tools to fix those issues.

My question is slightly different. I want to know if such randomly selected assemblies can become biased if someone tampers with the underlying randomness used to select its members, and if my recent work on certified randomness could help ameliorate this.

When I was little, I had this book by this obscure science-fiction author named N.P. Hard, and there was a story in the book I still remember. In a kingdom beset by political turmoil, the king abdicates, and a council of civic leaders decides to implement a lottery to select the next ruler. The queen is furious that her princely sons have been denied their birthright, and curses the machine the council intends to use for randomly selecting the next ruler. The lottery is conducted and — lo and behold — the eldest prince is chosen. Upon his death, another drawing, and again, his son is chosen. Generation after generation, the machine keeps returning to the same royal bloodline. In this way, NP Hard raises a question: was the lottery really fair? Is there even a way to check if it was fair?

I leave Procaccia’s office with an unsatisfying answer. Citizen assemblies happen rarely, and when they do, they come with public spectacle of a person physically drawing numbered balls from a jar. The chances of manipulation is minimal. However, if these sortitions took place behind the scenes and much more frequently, it would be worth investigating

I left Cambridge with a notebook full of notes. I love coming here. In New York, my conversations tend to be relatively dull and repetitive: restaurant openings, the vagaries of subway commute, marathon preparations, sample sales, Alo vs Lululemon, all the summer Shakespeare plays, and so on. But, in Cambridge, it seems that everyone has a grand idea, however removed from reality: a friend wants to reprogram every aspect of a cell; a man I met at a hotel bar is convinced the Buddha’s relics literally transmuted into precious gems (yes, the ones Sotheby’s is trying to sell). Here, one feels cloistered and sheltered, where ideas can flourish away from the caprices of the outside world.

Just last week, I was in D.C., having coffee with a friend who works for a household-name newspaper covering DC politics. I told him about my latest fascination—randomness, sortition, using math to optimize governance. And, we laugh grimly about it. How ridiculous it all feels! How utterly pointless!

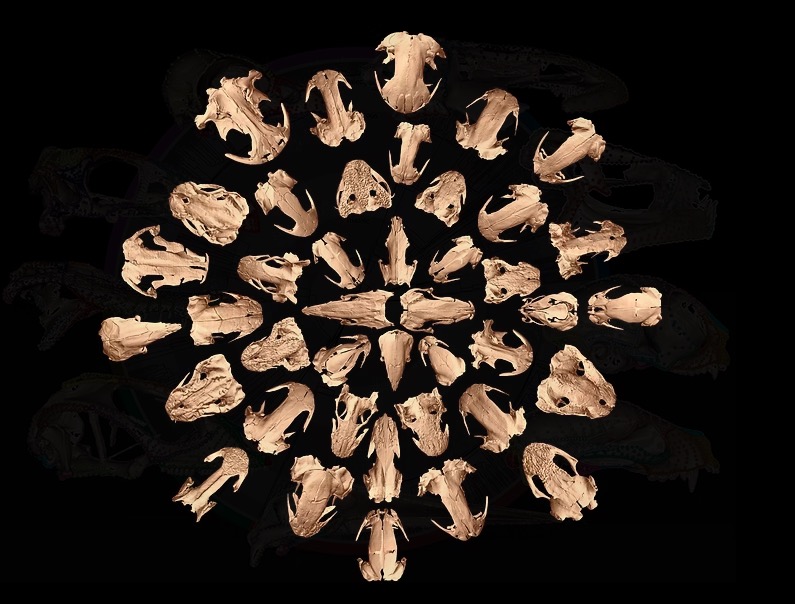

Whenever someone tells you they’re an experimental physicist, it’s usually safe to assume they spend their days smashing things together. So when a newlywed friend mentions me that his wife does biophysics with insects, I blurt out “What does she do? Smash bugs?”, partly out of instinct, but partly because, earlier in the week I had seen a Financial Times article titled “Inside the Large Hadron Collider for Smashing Bugs.”

Okay, so the headline is a little click-baity. No one is smashing bugs together. What’s being done is that a lab is using synchrotrons — devices traditionally used in particle physics to accelerate particles — to capture ultra-detailed 3D images of insects.

Book Recommendation: I’ve been reading Bluets by Maggie Nelson and find it absolutely beautiful. She uses poetic reflections on the color blue to talk about love, grief, and loss. Highly recommended.